|

|

|

|

In the Media

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Great thoughts speak only to the thoughtfull mind,

But great actions speak to all mankind." |

-Emily P. Bissell |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

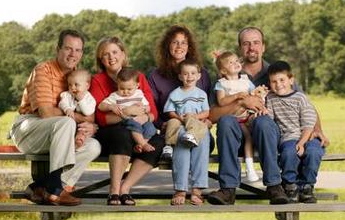

"I want them to know they have an extended family," says Bruce

Lindeman (left, with Susan and their twins) of the Lyonses

(right, with their twins and son Matthew).

|

|

|

|

Photograph by ERIC LARSON - Used with permission

|

|

|

After IVF, Glenda and Scott Lyons found a great use for their extra

embryos: They gave them to another couple. Now Susan and Bruce Lindeman

have twins, too - and they look just like the Lyonses.

As Glenda and Scott Lyons and their twins step out on their deck in Eau

Claire, Wis., to greet weekend guests - Susan and Bruce Lindeman and

their twin toddlers - the couples seem like college buddies who haven’t

seen each other for ages. The women hug, the men unload baby gear from

the car, and the adults make small talk - until Bruce says out load

what everyone’s been thinking: “Look at your Samantha! If our Chase had

hair, they could almost be twins!”

In fact, these people have never laid eyes on each other before, but

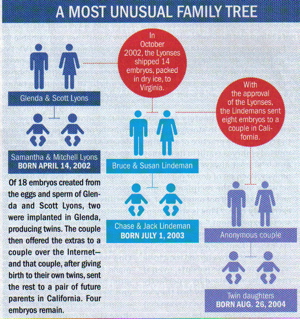

they share a unique kinship. Two years ago, after giving birth to twins

Samantha and Mitchell with the help of IVF, the Lyonses were faced with

a dilemma: What to do with the 14 embryos left over after the

successful procedure. Rather than discarding, storing or surrendering

them anonymously, as happens in most cases, the Lyonses took another

route. Relying on the Internet and instinct, they reached out to a pair

of strangers 1,000 miles away and - once convinced that the Lindemans

were the kind of people they could trust - sent them their extra

embryos. On July 1, 2003, when Susan Lindeman gave birth to healthy

babies Chase and Jack, the Lyonses celebrated too. The couples

exchanged e-mails and presents, and this summer the Lyonses took the

extra step of inviting the Lindemans to visit their home in Wisconsin,

where the couples and their two sets of siblings met face-to-face in

August. “I am beyond grateful,” says Susan Lindeman, 42. “There aren’t

any words that you can truly say to someone who has given you two

amazing children. Glenda and Scott gave us our future.”

|

Though approximately 400,000 embryos

are now in storage around the country, the practice of adopting unused

embryos is still in its infancy and is almost always done anonymously.For a set of donor parents to

actually meet the recipient couple and their kids is, if not

unprecedented, extremely rare. “This is still a giant social

experiment,” says Lori Andrews, a professor of reproductive law at

Chicago-Kent College of Law.“The children might grow up and want to be with their

|

|

|

genetic parents, even if

they’re being raised by a perfectly good family. They may feel they’ve

been given away. We don’t know what the ramifications will be.”

None of that mattered for the Lyonses. “No. 1, we wanted to know the

outcome of the adoption,” says Glenda, 35, a former accounting manager.

“Whether any children survived, where they were, whether they were

healthy. We just needed to know for peace of mind.” Married in 1997,

she and Scott, 37, a mechanic, already had one child, 6-year old

Matthew, when they found they were unable to conceive again and turned

to IVF. Doctors at Minnesota’s Center for Reproductive Medicine

implanted two embryos into Glenda in ‘01, producing twins. The couple,

who wanted no more children, were then asked by the clinic what they

wanted to do with the 14 embryos left over from the procedure. “Those

embryos deserved to live,” says Scott. Glenda agreed, with one caveat.

“We wanted to find the right home,” she says.

Glenda turned to a Web site she had used for support during her

fertility problems. Though the site forbids embryo brokering, she

inquired where she might donate embryos - and got 18 e-mail replies.

One was from the Lindemans. Susan, CFO of a Virginia baby-furniture

firm, and Bruce, 43, an IT consultant, were childless after three IVF

attempts. “It had been devastating for both of us,” says Bruce. The

Lyonses’ offer “felt like a divine intervention,” says Susan.

Glenda and Scott, meanwhile, were charmed by the Lindemans and even,

says Glenda, “their gorgeous English setter Joey. We’re dog-people,

too.” After just nine days, Glenda e-mailed Susan: “Good news. I talked

to Scott, and he agreed on choosing you and Bruce.”

For the next four months the women worked through the logistical

problems and had a legal document drawn up granting the Lindemans full

rights to any children born from the embryos. In October 2002, frozen

embryos shipped via FedEx arrived at the Lindeman’s Richmond clinic,

and 35 weeks later, Bruce saw his new son for the first time. “He was

holding my little finger, and I thought, “This is my child. No one can

tell me he’s not.’ Then Chase came, and it was the same thing.”

For the Lindemans the whole process was so positive that they have

passed along the favor. Last fall, after consulting with the Lyonses,

they posted an Internet offer and donated the eight remaining embryos

to a couple in California, who now have twin girls. For now, the

Lyonses and Lindemans agree that someday, when their children are old

enough to understand, they will be told about the special circumstances

of their births. Until then, “none of us can predict how this will all

turn out,” says Bruce. “It’s going to be fun. This isn’t the

culmination of something. It’s the beginning.”

Susan Schindehette. Giovanna Breu in Eau Claire.

Reprinted by special permission from PEOPLE Magazine's September 20, 2004 issue ; © 2004 Time Inc. All rights reserved.

Photos used with permission granted by photographer ERIC LARSON

cut

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nearly 400,000 embryos are stored in the United States,

88.2% are targeted for patient use, and

2.8% are available for research.

FERTILITY AND STERILITY | | |